Costard (Love's Labor's Lost)

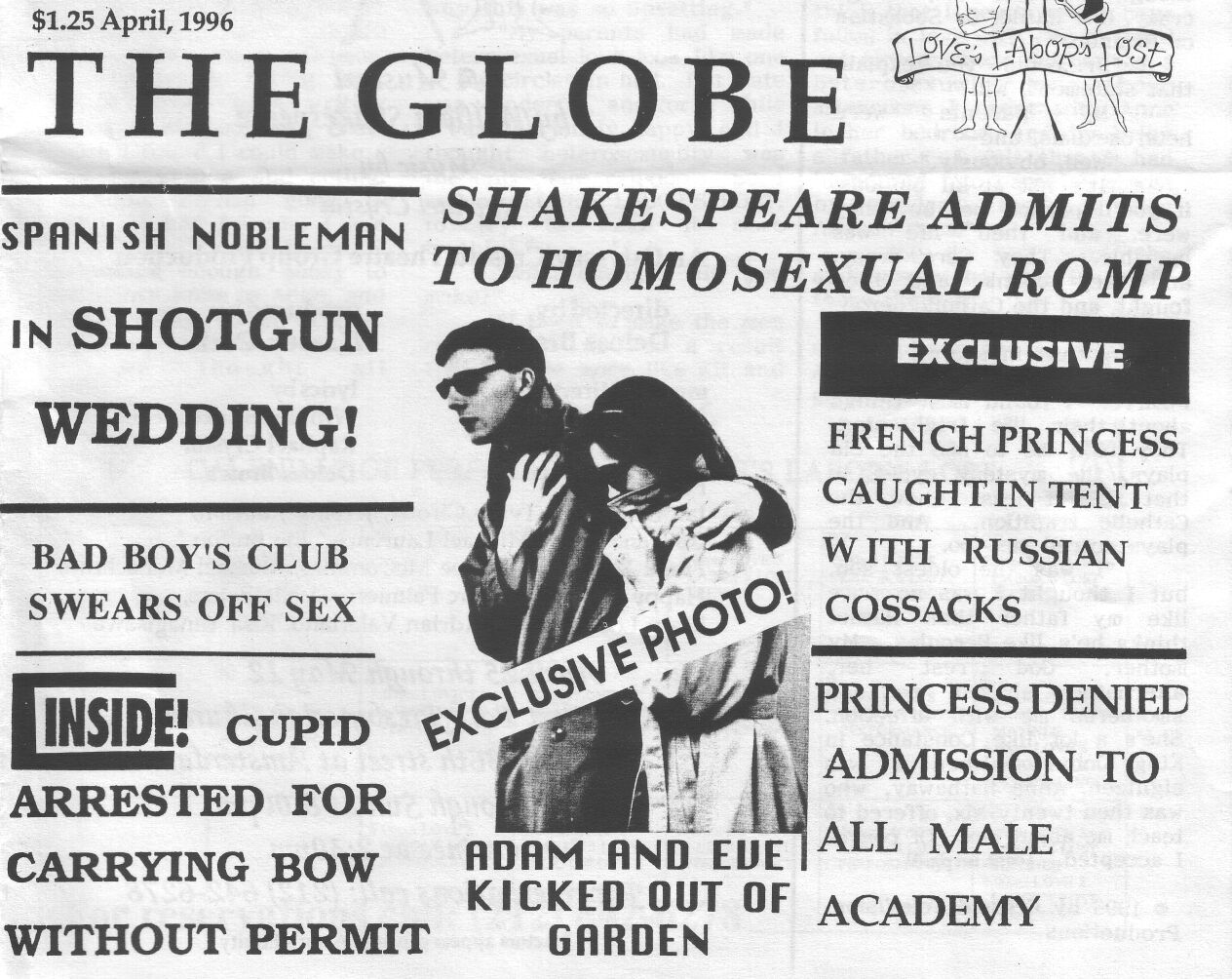

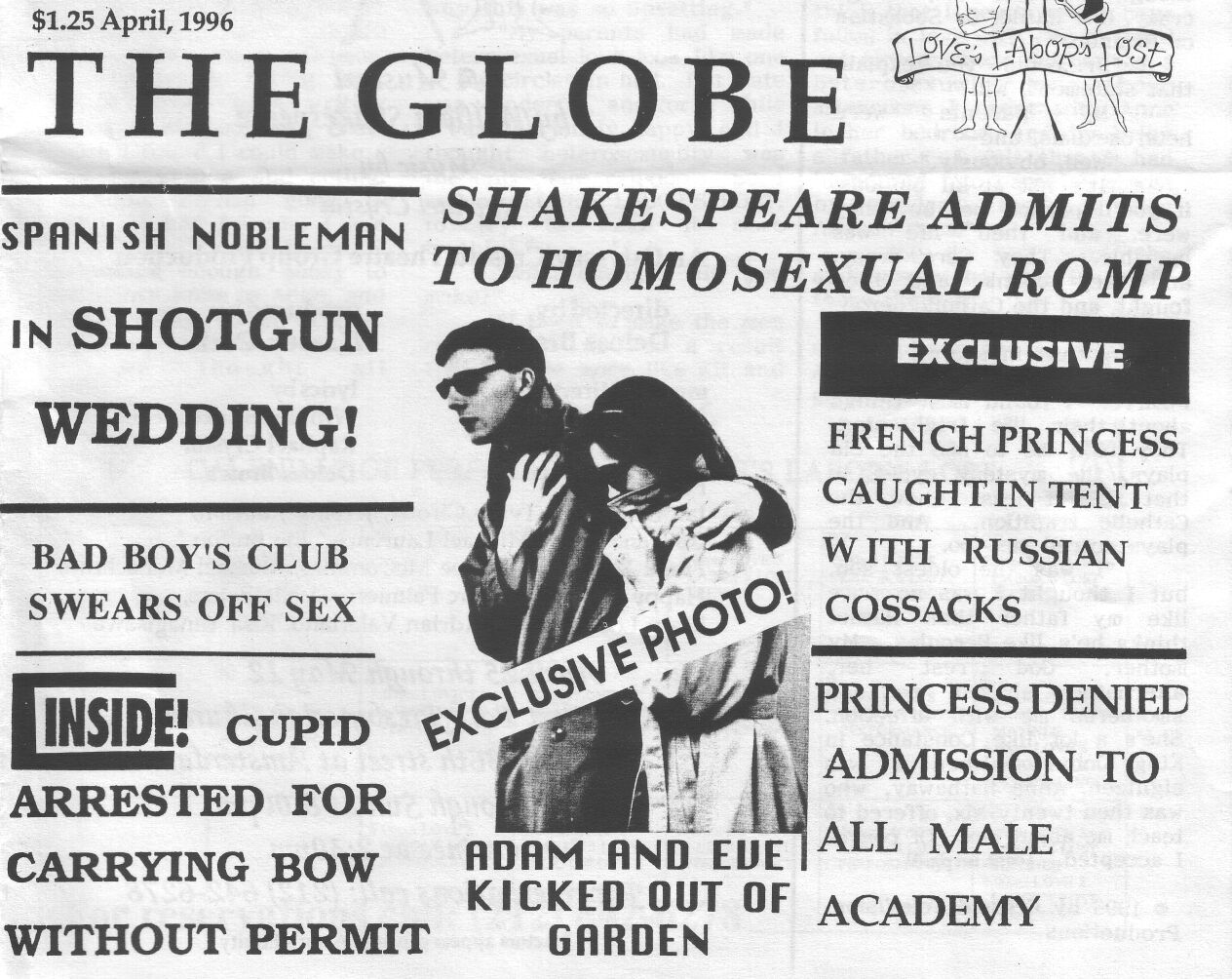

Raphael Crystal, composer, and I, began turning Love's Labor's Lost into a musical in 1996. We didn't get enough songs finished.

Raphael subsequently becane director of the musical theater program at Ball State University, and we finished the musical there: the students wrote the scenes, and Raphe and I wrote the songs. We had a couple of performances in New York, as showcases for the graduating class.

When a representative of New York's Most Famous Shakespeare Theater came to see the NYC production, he said, "Why did you make Costard so important?" I don't think we made him any more important than Shakespeare intended. Costard's journey through the play parallels that of the King and the Lords, but at his suitable unsophisticated (amd lower) level.

We did leave Costard onstage for Berowne's soliloquy, and gave him his own soliloquy about Jaquenetta while Berowne was complaining about Rosaline. But that's why musical titles ofent say "adapted from." Yes, Poulenc set Bernanos' play The Dialogues of the Carmelites practically unchanged to make his wonderful opera. But that opera is an exception. If you're adapting a work for a musical, or adapting another work for the stage, you quickly discover that structures hidden in the original work have to be made more prominent. (I have some experience with this, he said immodestly.)

The King and Lords are instantly smitten with the Princess and her Ladies. Yet they act on their love in a halting and disorganized way. They write the ladies (inept) sonnets and finally decide to entertain them with a production of the Pageant of the Nine Worthies. Almost everything possible goes wrong at the pageant, but the worst thing is the Lords' egregious and childish behavior in jeering at the performers.

Costard acquits himself pretty well in the pageant, accepting accurate if mean-spirited criticism (when he mistakenly and ribaldly says "Pompey the Big" instead of "Pompey the Great"). But then he learns that Jaquenetta has been made pregnant by Armado, and he challenges Armado to a fight, presumably to the death.

Obviously if Jaquenetta is already pregnant, it's too late in the game for Costard to compete for her affection. Why on earth did it take him so long? In the first scene in the play Costard is arrested for taking an interest in Jaquenetta.

COSTARD

The matter is to me, sir, as concerning Jaquenetta. The manner of it is, I was taken with the manner.

BEROWNE

In what manner?

COSTARD

In manner and form following, sir; all those three: I was seen with her in the manor-house, sitting with her upon the form, and taken following her into the park; which, put together, is in manner and form following. Now, sir, for the manner--it is the manner of a man to speak to a woman. For the form--in some form.

Well for heaven's sake--what took Costard until the end of play to try to win Jaquenetta? She's fond of him, or at least we can say, she likes his company:

HOLOFERNES

. . . Trip and go, my sweet; deliver this paper into the royal hand of the King; it may concern much. Stay not thy compliment; I forgive thy duty. Adieu.

JAQUENETTA

Good Costard, go with me. Sir, God save your life!

COSTARD

Have with thee, my girl.

(Exeunt COSTARD and JAQUENETTA)

And I suspect Costard is thinking about her when Armado gives him three farthings as a reward for being the postman for a letter--to Jaquenetta!

COSTARD

Now will I look to his remuneration. Remuneration! O, that;s the Latin word for three farthings. Three farthings--remuneration. What;s the price of this inkle? -- One penny.-- No, I;ll give you a remuneration. -- Why, it carries it. Remuneration! Why, it is a fairer name than French crown. I will never buy and sell out of this word.

(Enter BEROWNE.)

BEROWNE

My good knave Costard, exceedingly well met!

COSTARD

Pray you, sir, how much carnation ribbon may a man buy for a remuneration?

BEROWNE

What is a remuneration?

COSTARD

Marry, sir, halfpenny farthing.

BEROWNE

Why, then, three-farthing worth of silk.

COSTARD

I thank your worship. God be wi' you!

I find it unlikely that Costard is thinking about buying a hair-ribbon for anybody but Jaquenetta. So why doesn't he act on his amatory impulses? Probably because like all the other humans in the play--Armado perhaps excepted--Costard has no knowledge of cause and effect. It never occurs to him that it might not help his own relationship with Jaquenetta if he carries to her love-letters from Armado. And he never gets around to buying her a ribbon to tie up her bonny blonde hair (hi, there Devon!). He, like the Lords, and everyone else in the play, is easily distracted, until it's too late.

Armado, on the other hand, pursues his acquaintance with Jaquenetta to the point where he manages to get her pregnant. As a result, he and Jaquenetta are the only couple allowed to remain in the earthly Eden where all the characters started out--where they all, save Armado and Jaquenetta, failed to obey the promptings of love, and whence they are all, except those two, banished.

This is not a happy ending. But then, the name of the play is Love's Labor's Lost. Love's Labor's Won is a different play (see my articles in the Journal of the Cerise Press).

© Deloss Brown 2020

Back to CHARACTERS.